Reinventing hybrid collaborating organizations: The quest towards work - life harmonization

Update 1.2 - November 13, 2023 (Original version: April 28, 2023)

Today’s organizations need to be (re)imagined and (re)designed to be able to enhance their future readiness. Due to the worldwide COVID-19 pandemic, millions of people were forced to shift their lives and work into a ‘digital everything’-mode. Historically, pandemics have forced people to break with both the past and the present in order to refocus their view on the world. While the pandemic caused human tragedies and imposed severe restrictions on all aspects of organizations’ and people’s daily lives, it also provided a unique opportunity to conduct thousands of ‘forced’ experiments, innovate to some extent, develop new skills that could be applied to discover new – unforeseen and unknown – opportunities. The full impact of the shift to remote and hybrid work which the pandemic inspired may take years to understand.

On the one hand, people still believe that there is “nothing new under the sun” about the ‘New (Hybrid) World of Work’ - perspective: It is just “dressing up” the context in which people and organizations operate. On the other hand, there is a worldwide After-Covid transformation happening characterized by ‘irreversible discontinuity’ and/or disruption.

Such a massive transformation implies:

- “Once you get started, you won’t be able to put the ‘genie back into the bottle’ (Neal, 2018).”

- “Once the toothpaste is out of the tube, it’s going to be very hard to get it back in (Haldeman, 1976).”

- Few organizations will be able to go back - or forward - to a form of "normalcy" that somehow resembles the situation before the Covid-19 crisis.

A crisis often lowers the resistance to transform and therefore forces people to act - and stimulate organizations to get rid of deeply entrenched, dysfunctional practices that would be difficult to shed in ‘normal times.’ It also helps to let old habits die easier.

Hybrid and remote work may have been more productive than many CEO’s, managers, consultants and workers initially expected. By the other hand - due to the monotony of daily life integrating of work and home caused by the pandemic - many workers didn’t have the energy to think about much more than getting through the day. There’s a kind of formlessness in an always-on, remote world in which you can’t differentiate the weekend from any other day. After the pandemic, it’s no surprise that early 2023, the pressure form CEO’s and managers to reestablish the old habits of the - ‘office-based’ - productive routines’ became eminent: “But to the surprise of many, an intriguing number of old workplace habits, mainstays, and goals have reappeared, and they’re affecting all levels of the corporate lad¬der. Together, they suggest that even as the business world changes, it tends to cycle back to the norms of the past - albeit with some adjustments. Many of these old-school habits have changed in subtle ways that can be hard to track.” (Dahl, 2023, Back – with a twist. Korn Ferry Briefings – February/March, p. 27).

Leaders who force people back to the office risk pushing them into situations they aren’t comfortable with. In many ways, the offices people are being asked to return to are unrecognizable from the ones they left. Ironically, it’s the most casual aspects of the workday—the informal conversations and collaborations that were largely impossible when people were working remotely—that cause the most anxiety. There’s a lack of connectedness and kinship at the office. Many young workers who began their careers working remotely don’t feel a sense of solidarity with their colleagues. Management can make returning employees feel more comfortable by giving them a voice in creating the new office environment. Everyone is struggling with the current situation, so everyone should participate in designing a new one (Polonskaia & Boone, 2023). In their discussion (Hancock, Schaninger & Rahilly , 2023) on what’s at stake if leaders neglect the role of rituals in the workplace, Bill Hancock (McKinsey) believes that:

“It weakens the link to purpose. It weakens the link to the manager. And it weakens the ties across the organization. All three of those are critical for company performance, critical for retention, and critical for the well-being of individual workers. And we lose all of them (Hancock, Schaninger & Rahilly, 2023, p.7)."

1. Back into the Future of ‘Anyway, Anyhow, Anytime, Anywhere – Work’: Is your workplace where you are?

In 1997, Frances Cairncross published The death of distance: How the communications revolution will change our lives. This book was an extended version of The Economist survey of telecommunications using the same title (Economist, 1995):

“The death of distance as a determinant of the cost of communications will probably be the single most important force shaping society in the first half of the next century. It will alter, in ways that are only dimly imaginable, decisions where people live and work; concepts of national borders; patterns of international trade. It’s effects will be as pervasive as those of the discovery of electricity (Economist, 1995, p. 5, italics added)."

And that “increasingly organizations will locate any screen-based activity anywhere on earth, wherever they can find the best bargain of skills and productivity (Craincross,1997, p. xi, italics added).” Most people will have access to interactive networks:

“Companies will become looser structures, hold together mainly by their cultures and their communications networks. For individuals, the lines between work and leisure will grow less distinct. The design of the office and of the home will alter to accommodate the changing patterns of this communications-driven life Cairncross, 1997, p.4, italics added)."

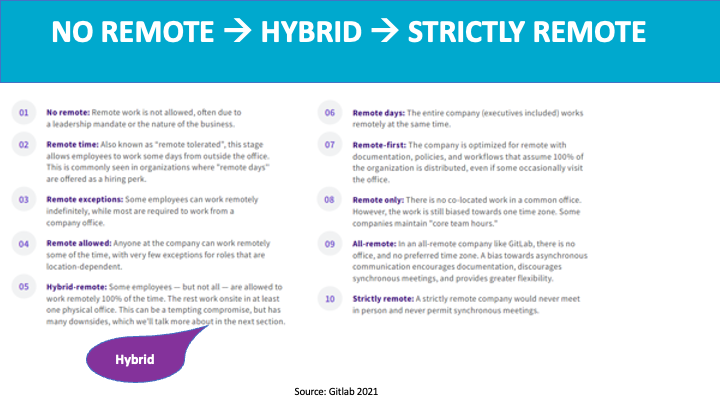

GitLab (2021) – an all remote company – is an example of a company where its organization design mindset accommodates the changing patterns of communications driven work & life. Gitlab has made a fundamental shift from an on - site presence work mindset towards an anyway, anyhow, anytime, anywhere – mindset (see figure below)

Organizations have been flirting with remote working since the early 1970s and 1980s. For example, in the 1980s the authors Stone & Luchetti (1985) stated that the design of (office) workplaces should take into account the concept of what the futurist Alvin Toffler called "electronic cottages". In this kind of (home) offices is a white-collar office employee connected through a computer to the office so that he or she can work from home. Ideally, office workers didn’t have to go to work to go to work. At the time, this was considered an aspirational vision of the office of the future. Their article was therefore titled "Your office is where you are".

In 2021 - 36 years later – due to the Covid 19 pandemic ‒ the promise of organizing and designing office work according to the concept "Your office is where you are" has become a global reality. However, to understand the full impact of this global ‘forced experiment’ on people, it is necessary to map the population of office workers by organization, region, country and continent. However, during the last 65 years, the amount of office - and knowledge workers were difficult to map (Lekanne Deprez, 1986, Davenport, 2005). A comprehensive overview of different types of workers includes:

White collar workers, pink collar workers, gold collar workers, office workers, data workers, information workers, knowledge workers, knowhow workers, gig workers, contingent workers, on-demand workers, transactional remote workers, free agents, nomadic workers, freelancers, contractors, knowledge professionals, hybrid workers, platform workers, remote workers, distributed workers, virtual workers, desk workers, satellite workers, telecommuters, liquid workers, infopreneurs, teleworkers, anywhere workers, nowhere workers, green collar workers, knowledge brokers, intelligence workers, laptop-class workers and so on....

Even in 2005, the US Bureau of Labor Statistics was not able to classify knowledge workers (Davenport, 2005, p.5). Due the imprecise definitions in the world of knowledge work and knowledge workers, Davenport (2005, p.6) has put U.S. workers into categories that can be (somewhat arbitrarily) defined as either knowledge workers or not. Davenport’s effort to classification produced “about 36 million knowledge workers in the United States alone, or 28 % of the labor force (Davenport, 2005, p.6).” Davenport (2005) concluded that now the US Economy is largely based on knowledge work and the effectiveness, productivity and value of knowledge work has become the key to the success of the US economy. While discussing the ‘Eight trends that will define 2021 and beyond’ (Huber & Sneader, 2021), Kevin Sneader – McKinsey’s global managing partner – stated that the global work-from-home (WFH) experiment during the pandemic sometimes gets discussed as if it applies to everybody, but let’s remember that it primarily pertains to advanced economies:

“Only about 25 percent of workers can do their jobs three days a week or more without being on-site. This is a group that takes a shower before they go to work. We cannot forget that most people take a shower after they have been at work, and there is a risk of a growing divide between those two groups (Huber & Sneader, 2021, p.4, italics added).”

Today, the pre – and post work showering rhetoric still applies. There is a distinction between hybrid/remote deskwork (pre-work showering) and deskless work (post-work showering). In advanced economies, more than half the workforce has little or no opportunity to work remotely. These deskless jobs (Bershin, Spratt, Enderes,& Nangia, 2021) often require frequent interaction with others - they chose their profession because of face-to-face contact with others - or the use of site-specific tools or equipment. Some jobs must be done on location, while other jobs are done while a worker is out and about, such as a taxi driver. Managers of deskless workers are often disconnected from the work itself and have limited insights into the interactions and behaviors of their workforce, because they themselves are usually desk bound.

Recently Bloom (Chui, 2023) indicated that in 1965, 0.4 percent of US people said they worked from home and didn’t commute, and that was growing. So that was 5 percent in 2019. That’s already about a 12-fold increase, running up to the eve of the pandemic. But then of course the pandemic happened, and that was an explosion. It went from 5 percent to 60 percent in the space of a couple of months. And it’s settled back down to 30 percent of days now are worked from home in the US. And it looks like that’s kind of where it’s ending up now (Chui, 2023)

Bloom (Chui, 2023): “Half the workforce, to be clear, can’t work from home. In fact, 55 percent in America do not work from home ever. They’re folks in McDonald’s, Chipotle, in hospitals, teaching, etcetera. The other half are mainly hybrid. That’s 30 percent. And then the remaining 15 percent are the fully remote (p.3 ).”

2. Is hybrid work here to stay … or is hybrid work a middle-of-the road approach doomed to fail?

Virtually all human achievements require the work of groups of people, not just lone individuals (Malone, 2018). Organizations are collectives, involving people who participate in coordinated action. Creating value is achieved not only by what people know, but also by who they know and who knows them. A collaborative organizational form will avoid fragmentation and will institutionalize an ethic of contribution. An ethic of contribution is a “shared conviction that the most important virtue is contributing to the achievement of the organization’s purpose” (Adler & Heckscher, 2018, p.93). Every organization should have a purpose and a unique set of values that drive its reason for being here, it’s sustainable growth and success.

“Once upon a time, people lived in framed periods of work and rest, dictated by seasons and religion. Meanwhile, our whole life has become one big productive performance; everything we do must be optimal, serving a purpose. (Smithuijsen, 2023).

In their report From Quit Quitting to Conscious Quitting, Polman et al (2023) surveyed 4000 workers in the US and UK and around half say they would consider resigning if the company’s values don’t align with their own. More and more people are distancing themselves from organizations whose core values don’t match their personal values. Does an organization help people to grow? Or better, does the organization intentionally develop people from where they are today to where they aspire to go (Green, D. 2023 -Inspired by Daniela Seabrook, CHRO at Philips)? The phrase ‘we are the organization’ must be significant for creating a great place to work where people often instill pride in their organizational membership, organizations have a positive impact on the world and what they personally contribute to the purpose of the organization.

In an interview with JPMorgan Chase’s head of global real estate David Arena, McKinsey Partner John Means (McKinsey Partner) asked him: “These days, we’re constantly talking to companies about how every office needs to have a purpose. What’s the purpose of 270 Park Avenue (= JPMS HQ address)?”

According to David Arena, “We believe that when we are together in a place and that place is purpose-built and we’re there together for the moments that matter, we can’t be beat. This office has lots of reasons for being. The first and foremost is it’s a house for employees. It’s a house for people, it’s a house to bring clients to, to bring guests in, it’s a place to do business. It’s the manifestation of the brand in the physical environment. Everything you look at, everything you hear, smell, taste, touch, is part of JPMorgan Chase and part of that experience. You could say it’s a place to have an experience. It’s a place for our senior-most people to lead their teams, and it’s a place for people to come to work, to be with one another, to share culture, to share knowledge, to cocreate the future of their businesses, and to bring dreams to life for their clients (McKinsey & Company, 2023) .”

Due to the Covid crisis, employees want more choice and control over how, when, and where they work. Flexible work is associated with increased productivity and focus, not less. If employers respond by measuring worker performance and productivity by how many hours employees spend in the office (i.e. the old industrial mindset), they’re likely to drive away top talent and miss the opportunity to increase productivity (Future Forum Pulse, October 2022).

In the early 20th century, physical offices were places where - often many – people are gathered together to work on paper-related tasks. In the 1980’s, only a small part of the white collar office work could be labeled as ‘work where they are’ - e.g. insurance salespersons may have a filing cabinet in an office somewhere, but their real ‘base’ was their car. Nowadays, the physical office environment is important to focus, ((inter)connect, learn, collaborate and spend time together with colleagues. The office as a place has converted into a setting to (re)connect with colleagues gaining networking skills, engage in social activities, and reignite the interpersonal interactions. Although at the start of the pandemic, the shift to all remote work and hybrid work appears to have happened in the blink of an eye, the demand for more flexible work arrangements and a good work-life balance had been manifest for many years.

Often, value creation is the result of valuable interactions. It is a group/team/community/network/micro organization - based process of working “with one another for each other” (adapted from Pflaeging, 2014, p. 47). It’s all about connecting, cooperating and collaborating with everyone from everywhere to create value. For the concept of value, many different definitions have been offered (Fjeldstad & Snow, 2018; Järvi et al., 2018; Mazucatto, 2018).

An organization matches its value proposition (Lanning, 1998; Taylor, 2016) – i.e., a clear and simple statement of the benefits, both tangible and intangible, that an organization can provide while doing things that others cannot or will not do – to what customers, clients, citizens, and other relevant stakeholders actually value.

People often think that they create value, but actually they often extract value from nature, from resources (energy, food materials, water), and ….from human beings. It is critical to unlock the – often hidden - value. Furthermore, it is crucial to determine whether what has been created is in fact useful (Mazzucato, 2018) and whether people are willing to pay – in the form of attention, money, goods, effort, sharing, impact and so on – for the goods, services, and experiences. Increasingly the business purpose of organizations includes the flourishing of people and the planet. Connecting such a purpose with management practices often contributes to a mind shift: from ‘being the best in the world’ towards ‘being the best for the world’.

Anytime a colleague, customer, client or citizen interacts with your organization, an individual is engaging an experience. Each interaction represents an opportunity to enhance value by turning even ‘mundane’ transactions into memorable nextperiences that will engage colleagues, customers, clients and/or citizens.

3. Hybrid work: Get your interact together!

Organizations all over the world are still in the process of figuring out how to successfully develop hybrid workspaces. In the world of hybrid work, flexibility is highly desired, second only to compensation when it comes to workplace satisfaction and employee engagement. But while most conversations about workplace flexibility have centered on location - where people work - the question of when people work may be even more significant. While 80% of global desk-based workers say they want location flexibility and 94% say they want schedule flexibility” (Future Forum Pulse, October 2022, p.12).

In their quest for defining hybrid work within hybrid collaborating organizations Van der Velden & Lekanne Deprez (2023) follow the path to three recent stages that may have led to a paradigm shift in working practices, mainly induced by the lockdowns during the COVID-19 pandemic. Before the lockdowns, stage 1 (from March 2020 onwards), most collaboration activities took place in an onsite setting. During the first lockdown, stage 2, the ‘forced’ lockdown collaboration took place in a remote setting (March 2020 – August 2020). The 3rd stage (September 2020 – February 2022 ) is portrayed as a hybrid setting - combining the two contexts of the first and second stages - where management is partnering with employees on an individual basis what works best for them, allowing individuals to have autonomy to create their own paths. Once employees were no longer tied to a physical workplace, they are demanding location and schedule flexibility:

Managers lost the close control that they used to have over employees’ performance and behavior—and employees began to realize that they could tap a greater range of job options, far beyond commuting distance from their homes. These changes were liberating, but they placed even more of a burden on managers and bosses who now were also expected to cultivate empathetic relationships - to become ‘boaches’ - to engage and retain the people they supervised (adapted from: Gherson & Gratton, 2022).

After the pandemic, people of different generations, demographics and ages wanted different things based on their stage of life needs and past remote & hybrid work experiences:

“Hybrid for me — and millions of other employees — can mean working from home when I'm not in the office, but it can just as easily mean working from any of these other locations: Airplanes, airports, automobile (driver or passenger), business events, branch offices, community events, company functions (e.g., picnics), conferences/trade shows, co-working space, customer facilities, offsites/retreats, festivals, restaurants/coffee shops, satellite offices, beach clubs, and so on (adapted from Gullo, 2023)”.

Early 2023, Frank Gullo (2023) - Chief Technology Officer for Aleron Group - concluded that there will never be a universal standard for hybrid work because there is no one-size-fits-all solution — and that's OK. As hybrid work is idiosyncratic, every organization has to find its ‘own rhythm’, and design its ‘own hybrid collaborating organization’(Van der Velden & Lekanne Deprez, 2023).

“Our approach to hybrid work was always from the start that we want our people to spend more work together than apart, so that was a very deliberate choice. And in that respect, we always had the approach that people should come and meet physically, should be more regularly in the office, and also should be affiliated to one of our Philips offices, rather than be entirely remote. Of course, we have people who are entirely remote; we have people dependent on roles where this is possible, but overall we put emphasis on, ‘You need to be close to an office, you need to come and interact with people, and particularly also linked to your job’. Then I think this issue probably becomes a bit smaller. we gather a lot of data why people are leaving; and the number one reason in our case, and probably that's common across companies, is the lack of career progression (Green, 2023 Inspired by Daniela Seabrook, CHRO at Philips, italics added)”

In general, hybridity denotes the blending of features that are assumed to be distinct. The focus will be on hybridity as the combination of multiple organizational forms. This approach to hybrid organizing (Battilana et al., 2017; Battilana & Lee, 2014; Kolbjørnsrud, 2018) builds on the long-standing interest among organizational theorists in how organizations respond to the tensions between competing forces that are inherent to organizational life. In business settings, hybrids involve two or more organizations that work together - i.e., share, cooperate or collaborate (Kelly, 2016) - to achieve an agreed-upon mutual goal. Hybridization - in which several forms are combined depending on specific needs - can come in two forms: “One is mixing elements of different forms, another one is using multiple forms within one organization but in different parts of the firm” (De Man et al., 2019, p.207). The organization form that works best for any organization depends on many variables. Organizations can learn from other design options but, in the end, they must reinvent or reimagine their ‘own’ form.

Van der Velden & Lekanne Deprez (2023) believe that hybrid organizing should not only be perceived as an employee-driven choice, but also as a strategic management choice. Management will be fostering an organization-wide culture of trust moving from span of con¬trol & narrow supervision to span of support & guidance and feedback to really work together in a creative and innovative process to generate concepts, try it out, don’t hold them back, unleash their potential, allow them to fail, and the manager is there to support. Admit that the organization is experiencing things that we have not experienced before, and it is okay to say we don’t know. Both choices will pave the way for realizing its desired level of sustainable performance. As hybrid work is idiosyncratic, every organization must discover its distinctive matching hybrid work collaborating organization to improve its performance, employee involvement and innovation power. In order to steer the transition to a hybrid work collaborative organization in the right direction, a number of issues follow that need to be taken into account. Organizations are only as ‘productive/creating value’ as the quality of the interactions that take place among people. This implies that leaders and managers in the remote and hybrid world of work must shift their focus from getting their act together into getting their interact together.

Recent research on determining the best practices of hybrid work by Arena et al (2022) and Arena (2023) examines the interactive collaborative process of binding and bonding. In the report “How to make hybrid work effective, engaging and empowering”, Arena’s (2023) team studied hybrid work to determine best practices and figure out who is right about remote and in-person work. What Arena and his team (Arena, 2023) found is that everyone is right and everyone is wrong. Remote work is not all as bad as Chase CEO Jamie Dimon and Tesla CEO Elon Musk would have people believe. Both Dimon and Musk have said remote workers are unproductive.

They both enforced return to office policies as soon as the pandemic was more manageable. But there are limits.

“Hybrid work can be an effective alternative, but leaders must organize it in a way that allows employees to effectively connect and increase productivity and success (Arena, 2023, p.2).”

An intentional hybrid model helps bonding and bridging connections. To understand how the shift to remote and then hybrid work is transforming the workplace, observers must grasp the difference between human and social capital:

- Human capital: The summarization of one’s skills, experiences, and knowledge

- Social capital: How well one is positioned to leverage these attributes

What the world learned during the pandemic is that how we are connected is critical to determining work outcomes, including productivity, innovation, and cultural development.

Social capital types determine how people on a team connect with one another and whether they are cohesive. As a result, two social capital types became paramount:

- Bonding Social Capital - helps to facilitate in-group interactions

- Bridging Social Capital - helps to facilitate across-group interactions

Both types of connections are critical to long-term success. Strong bonding social capital enables a team to move fast, as one cohesive group, executing and quickly iterating by sharing ideas, challenging assumptions, and building better products with trusted peers. The result is often greater productivity and better tacit learning.

In contrast, strong bridging capital provides access to novel and diverse sets of information, making it essential for the creation of new ideas and breakthrough insights. Bridging connections also provides access to resources outside an employee's immediate team that help to facilitate scaling and adoption activities.

Understanding these nuances is critical. The loss of a few critical – key - employees in networks can create substantial network fragmentation. While on the other hand, a few central employees moving from one part of the network to another, can quickly fuse together two previously separated groups:

”Consider an engineering organization of 700 people, who had a dense set of bonding connections and strong bridging connections before the pandemic forced remote work upon them. In observing how the organization evolved in the years since spring 2020, one notices that being apart for so long caused a deterioration of the bonding and bridging social capital. When the pandemic first hit, businesses could sustain themselves because everyone knew each other, they were in it together, and they could leverage the previous bonding and bridging to get through working remotely. Bonding capital increased 40% among close collaborators in those early days of the pandemic. Over time, people left the team, new people arrived, everyone continued to work with each other from a distance, and it caused a 25% drop from bonding at its peak.

After prolonged remote work - nearly 12 months into the pandemic - the erosion of both bonding and bridging social capital has begun. So a year into the pandemic, things looked different for that engineering organization. Over time, distinct clusters emerged and they could be isolated and somewhat detached from the organization’s overarching mission. In other words, people lacked direction and that ever-important sense of purpose. It resulted into:

- Limited access to new ideas

- Greater insularity

- Decrease in trust, which leads to slower speed and execution

- Less learning from one another (adapted from Arena, 2013)”

Throughout the pandemic, as many organizations have been forced to work virtually, most organizations have morphed from relatively cohesive networks structures that are broadly diffused, to socially disconnected neighborhood structures that are more dependent on a limited set of local interactions.

As more distinct clusters emerge, these groups become more detached from one another and from the broader organizational purpose. The neighborhood effect has limited our ability to work broadly and dive deeply in a hybrid context, and it has placed both innovation and complex problem solving at risk. Some practical solutions to overcome this neighborhood effect are:

- Establish formal structures and methods to reinforce collaborative practices across the organization.

- Connect with a few primary bridging people, who have a strong feel for politics, social dynamics, and the resources and expertise across the organization.

- Ensure that the individuals with the most bridging power do not become overloaded with collaborative demands by leveraging collaboration analysis techniques and reviewing social burdens to distribute them in a more equitable manner.

- Leverage leader’s existing social equity because it is easier to activate dormant connections than it is to build new ones.

- Understand the implications of the neighborhood effect and study the few positive deviance cases that exist (Arena, 2023, p.10).

Within this context , Van der Velden & Lekanne Deprez (2023, p.49) propose that:

“As collaboration is the driver for increasing performance within hybrid work collaborating organizations, poorly designed physical and digital collaborative organizational forms will hamper the quality of collaboration (Boughzala & De Vreede, 2015; Cross & Carboni, 2021; Leonardi, 2021; Yang et al., 2022), productivity (Cross & Carboni, 2021; Leonardi, 2021) and the loss of spontaneous interactions. Especially the loss of watercooler moments in the virtual world where chance encounters have been replaced by “overconnectivity” forcing members of teams/communities/networks to connect more often, squeezing even more scheduled meetings in a day. In such an overconnected world with more meetings, people become overloaded living within the limits of their attention’s resources. Within such organizations, “go-to” persons are being increasingly required to contribute repeatedly, there is a risk of them becoming overwhelmed, emotionally drained and /or burned out. Prioritize the time they spend on focused work and encourage to set boundaries to protect it (Cross, 2021; Cross & Carboni, 2021).”

4 From Third Place to Third Space & Coworking Space

In 1989 the sociologist, Ray Oldenburg, released an influential book The great good place. Cafes, coffee shops, community centers, beauty parlors, general stores, bars, hangouts, and How they get you through the day, in which he coined the concept of Third place. The concept Third place – introduced in 1982 (Oldenburg & Brisset,1982) - identifies places which are not home (First place) or work (Second place), but are ‘informal public gathering places’ (Oldenburg 1997,p.6) such as cafes, clubs, public libraries, or parks. Increasingly internal company work environments include what might be called third places (on-site cafés, coffee and juice bars, creative space, and other gathering places).Oldenburg has identified 10 important functions of great, good places (see below). In the Steelcase Company 360 (2014) article the ones that apply to internal company third places are ‘starred’:

- Promoting democracy

As John Dewey once put it, “The heart and final guarantee of democracy is in the free gatherings of neighbors on the street corners to discuss back and forth and converse freely with one another.” - * Neighborhood unit*

Local gathering places allow people to get to know others in the neighborhood. Bonds are formed. People learn who can be counted on for what. Suspicion of neighbors is eliminated. - * Multiple friendships*

The only way one can have many friends and meet them often is to have a neutral-ground gathering place nearby. The more friends people have, the longer they live. - Spiritual tonic

Joie de vivre or la dolce vita cultures derive from frequent sociability in the public realm. These are most easily identified by an abundance of sidewalk cafés in their cities. - Staging area

When Hurricane Andrew hit Florida, many people, eager to help, didn’t know where to go as there were no gathering places in the neighborhoods. In times of disaster, unofficial aid comes well before official aid and is often of greater importance. Third places, in this context, allow people to help one another. - * Generation of social capital*

People with diverse skills and interests come to know and trust one another. This has a positive effect on the economy. In the Old South, regions that permitted taverns were better off economically than regions that did not permit them. - Lower cost of living

Third places typically bring together diverse occupations, talents and skills. What a person needs help with is one of the first topics of conversation in the group, and if one or more members of the group can lend a helping hand, tool or advice, they will. Most of the people one meets in a third place may be categorized a “weak ties,” and in many ways they are more helpful than close friends, for example, in finding a job. - Enhanced retirement

The need to “get out of the house” after retirement can be met daily if there is a nearby third place. - * Development of the individual*

The location of the home and the nature of the workplace keep us in regular contact with people who are similar to us. Third places bring together people of different occupations, backgrounds, socio-economic standing and viewpoints. From these people we learn about the world we live in and how to get along better in it. - * Intellectual forum*

The issues of the day and many other matters are discussed regularly and informally, but not chaotically. Participants learn to think well before it’s their turn to speak.

Our work/lives are acted out in three broad contexts:

- First Space - home: private space of individuals, families and communities;

- Second Space – work: work space that generate social and economic resources;

- Third Space – (virtually) integrating home, work and other spaces depending on the function space serves.

In an interview within Steelcase’s 360 Magazine(2014), Oldenburg maintained that third places are face-to-face phenomena:

“The idea that electronic communication permits a virtual third place is misleading. ‘Virtual’ means that something is like something else in both essence and effect, and that’s not true in this instance. When you go to a third place you essentially open yourself up to whoever is there.”

According to Oldenburg (Steelcase 360 article, 2014), the most effective ones for building a real community seem to be physical places (public houses; hang outs) where people can easily and routinely connect with each other: parks, community centers, churches, public sports facilities (e.g. tennis, soccer, football, hockey etc..). Nevertheless, creating highly effective and appealing in-company third places within organizations involves more than instant access to good coffee and tea, healthy food, Wi-Fi, informal communication (‘gossip’) and sports facilities. For Millennials (born 1980 – 1994), Generation Z (born 1995 – 2012) and Generation Alpha (2013 – 2025) many ‘digital connected places’ have evolved into (virtual) spaces of activity. These Third spaces of activity such as Facebook, What’s app groups, online (text) chat rooms, TikTok , Spotify - including dedicated ‘special event’ apps (e.g. Tomorrow Land, Formula 1 , Ajax, Manchester United, Justin Bieber, Depeche Mode, Vinyl Records, etc..).. These places are (dedicated) spaces and/or platforms which provide opportunities for people – according to Oldenburg (1999) - to meet and interact, have informal face-to-face contact, being socially connected, exchange ideas, have a good time, build relationships and develop a sense of belonging to place. People are feeling ‘home away from home’ where weak ties are nurtured and creative spaces – “spaces that inspire” - are flourishing to become important inspiration for hybrid collaboration organizations to focus on binding and bounding (Arena, 2023) processes. Third Space focus on creating an environment that supports the wellbeing of people physically, cognitively and emotionally by integrating – or even harmonizing - work & life activities. As a result many traditional ‘brick-and-mortar’ third places’ ( e.g. community centers, churches) are being reimagined – or ‘repurposed’ - as people increasingly go digital for their business & social network connections.

Also coworking ( Merkel, Avdikos, & Pettas, 2023) offers an alternative between the home office and traditional company office. Examining the various definitions of coworking in Table 1 (Kraus, Bouncken, Görmar, González-Serrano & Calabuig, 2022, p.3), they all have in common that they highlight the physical space as the differentiator. However, these definitions emphasize different aspects of actions that take place in these physical spaces. Moriset (2013) definition is an exception who stated that coworking is an atmosphere. This definition refers to the community as the core of coworking. Coworking encompasses sharing the physical space and going beyond, including sharing as a form of social support or collaboration. Not everyone is willing to collaborate with other individuals in a shared space (Rese, Kopplin, & Nielebock, 2020). Thus, it is essential not to limit the definition of coworking on collaboration. As a result, the definitions of Spinuzzi (2012) and Papagiannidis and Marikyan (2020) fulfill the characteristics and can explain coworking the best.

Source: Kraus, Bouncken, Görmar, González-Serrano & Calabuig, 2022, p.3.

In brief, coworking can be bound to a physical shared space of individuals who do not necessarily share the same employer. Moreover, social interactions and a resulting community are vital characteristics of coworking. Moriset (2013) proposed a different definition, but he highlighted the sense of community in coworking spaces. Interesting is the perspective of coworkers who perceive coworking as a global movement (Gerdenitsch, Scheel, Andorfer, & Korunka, 2016; Servaty et al., 2016) and underline five distinct core values of coworking: Community, openness, collaboration, accessibility, and sustainability (). These values originate from the coworking space “Citizen Space”, one of the first coworking spaces worldwide (Waters-Lynch, Potts, Butcher, Dodson, & Hurley, 2016).

5 The right to disconnect – Do fewer connections lead to better relationships?

The right to disconnect refers to legislation that allow workers to disconnect from their work and to not receive or answer any work-related emails, calls, or messages outside of normal working hours. It establishes boundaries between a person’s work and life, and protects them against any negative repercussions for disconnecting from their job (Capital Global Employment Solutions, 2023). During the pandemic, people’s personal and professional lives became blurred and as a result they worked longer hours by being part of the Triple Peak workdays (Microsoft, 2021). With the growing ‘always-on’ culture where workers are expected to respond to emails, phone calls and texts after work has ended, not only more legislation for disconnecting from work needs to be in place, but also human centric people management that supports radical flexibility options regarding where, when and how to harmonize work/life (see also – next paragraph).

Nowadays people enter a digital world full of distractions that seduces people to do ‘multi- tasking’ in their work – life spaces. Combining email responses while helping children with their homework or being in multi -virtual meetings ‒ supported by Zoom, Webex, Microsoft teams…. At the same time. These activities are able to decrease – or even destroy! – the ability to focus making work less productive and life less meaningful. These distractions invade not only the work life of people, but also the private lives of family members that are increasingly living on a treadmill of continuous checking email, What’s app messages, TikTok, Podcasts, etc.. People are increasingly overwhelmed by the amount of –asks and responsibilities that apparently requires immediate attention. Sometimes it is recommended to distance yourself to see things more clearly or restrict yourself to single tasking to be able to reclaim your work/life and improve life itself: ”At any given time you can do one thing well or two things poorly (Zack, 2015, p.14). Also multitasking creates busyness that’s hacking your (work)life’. The challenge is to regain focus on what is needed or required within First -, Second – and Third Space: After all, if attention goes one place/space, then it can’t go another (Paraphrasing Davenport & Beck, 2001, p.11).”

6 Nextperiencing working and living in a post-pandemic world: Integrating First-, Second- and Third Space within hybrid collaborating organizations

Human work/life and behavior are always situated in particular place and/ or space (Lekanne Deprez, 2016). Place often represents the “here and now of immediate perception” (Ford & Harding, 2004, p. 817) and is associated with a sense of being. Space on the other hand generally represents a certain broadness of perception and is associated with becoming and with a constant drive for newness and growth (Schulze & Boland, 2000).

Oscar-winning movie director Robert Altman once stated that “The role of the director is to create a space where actors and actresses can become more than they have ever been before, more than they have ever dreamed of being.” (Peters, 2023, p.6).

Within organizations, people will not only exploit the opportunities of space for their mutual benefit, but they will also create barriers and boundaries that might hinder their performance, growth, and/or sustainable development. Boundaries should not be considered as negative or limiting per se. In space, boundaries are drawn again and again. Apart from tangible boundaries—such as gates, walls, budgets, and programs—most boundaries are unclear, invisible, virtual and at best blurred. Organizations are particular kinds of space, in the sense that they embrace human behavior.

Organizational spaces are designed with a purpose in mind. They succeed (or fail) to the extent that these ‘spaces’ evoke the desired behaviors from their ‘members’ necessary to achieve the organization’s purpose (Liedtka & Parmar, 2012). During the Covid pandemic, however, many members of organizations were forced to transfer their work activities from Second Space (office: in – person ) to First Space (home: ‘remote first & virtual setting’). Having more than one ‘office’ within First, Second & Third Space made employees feel like they’re always on the clock — there is no designated work-free zones. After a while people increasingly get the feeling they’re living at work.

When it comes down to performing in hybrid collaborating organizations, the state of the art regarding supporting digital support systems has progressed but must be improved. Leonardi (2021) believes that digital collaboration tools not only provide a space for employees to work together but also make that work and its history visible to other people within the company: “Digital collaboration tools serve two main constituencies within a company:

- Regular collaborators interact frequently, often on projects and rely on one another to complete their day-to-day work. Typically, employees know their regular collaborators relatively well. These colleagues can be team members, project sponsors, managers, or mentors.

- Sporadic collaborators seldom interact and do not know one another well. They are not teammates but may have knowledge or information that is directly applicable to one another’s projects. An employee’s sporadic collaborators might include coworkers who occupy similar positions in different business units or people who work on similar problems in different regions or functions (p.15) ”

The best tools for solving the collaboration problems created by digital change will depend on the type of collaborators involved. Although the two types of digital collaboration tools — teamwork platforms and broadcast platforms — make it easier to overcome boundaries and other obstacles to collaboration, not all employees will see such value from day one. It takes time to spot and capture the activities of regular and sporadic collaborators to accumulate on both types plat¬forms. At the start of the pandemic (early 2020), employees were ‘forced’ to work from their First Space (home) by virtually connecting to others using digital collaboration tools (Zoom, Webex, Microsoft Teams etc..). With these kind of collaborative technologies ‒ that were massively rolled out during the pandemic ‒ organizations ensured that nobody got ‘left behind’.

The biggest struggle working in a remote & hybrid way stems from the erosion of work -life boundaries and the blurred lines between First Space (‘personal life’) and Second Space (‘professional life’). Once Second Space activities were integrated in First Space (Home), there was a danger that designated ‘work-free zones’ disappeared.

Microsoft (Microsoft, 2021) has indicated that the shift from full-remote work to post-pandemic hybrid work arrangements has given rise to the so-called hybrid-work paradox. Satya Nadella (Nadella, 2021)—Chairman & CEO of Microsoft—believes that “every organization’s approach will need to be different to meet the unique needs of their people. According to our research, the vast majority of employees say they want more flexible remote work options, but at the same time also say they want more in-person collaboration, post-pandemic” (p.1). In other words, a successful shift to hybrid work will depend on embracing the hybrid paradox, in which people want the flexibility to work from anywhere, anyhow, and with whom, but simultaneously desire more in-person connections. There is no single organizational design methodology that works well under all circumstances.

Each organizational design effort can be considered an experiment and opportunity to learn. In business settings, hybrids involve two or more organizations that work together—that is, share, cooperate, or collaborate (Kelly, 2016)—to achieve an agreed-upon mutual goal. Hybridization—in which several forms are combined depending on specific needs—can come in two forms: “One is mixing elements of dif¬ferent forms, another one is using multiple forms within one organization but in different parts of the firm” (De Man et al., 2019, p. 207). Hybrid work collaborating organizations can learn from other design options but, in the end, they must reinvent or reimagine their “own” blended form.

With regard to hybrid work collaborating organizations, the focus will be on hybridity as the blending of remote first (office occasional) and office first (remote allowed) work arrangements. In organizations, people not only want and value the flexibility of “mixing” these two work arrangements but also include room to move (where, why, how and with whom they want to work) and their room to grow. If not, people will vote with their feet: “If we’re not growing, we’re going.”

7 From work-life balance towards work-life harmonization: life is work & work is life

I like work, but there is more in life

At the start of the pandemic, when everybody had to confirm to the ‘remote work only’- option, many desk workers wondered:

“How do I stay true to both my work AND my family?” (Golden, 2021, p.1)

During the COVID-19 crises, when most desk workers were forced to spend substantial time virtually working from home, people were reexamining their individual purpose by questioning what matters in their ‘work - life’:

“We lose ourselves in work, and rediscover ourselves in life. We survive work, but live life. When work empties us out, life fills us back up. When work depletes us, life restores us. The answer to the problem of work, the world seems to say, is to balance it with life. Of course, we are simplifying here ((Buckingham & Goodall, 2019, p.184).”

In the current hybrid world of (desk)work, neither ‘your work’ or ‘your life’ are in balance, nor will they ever be. When work takes over, people experience stress, depression, anxiety, burn out and so on. Work - life balance signifies trade-offs: gaining in one area at the expense of others (Friedman, 2008, p.14). In his book The Energized Workplace, Timms underlines that “there is no work-life balance, only a balanced life (Timms, 2020, p.99).”

In order to ‘get a balanced life’ each of us has to challenge the status quo by negotiating a set of unique radical flexibility options. Mortensen & Edmondson (2023) suggest to offer employees more than flexibility by rethinking the Employee Value Proposition (EVP). This proposition includes four interrelated factors: Material offerings (including compensation, perks, physical office space), opportunities to develop and grow (including acquiring new skills), connecting and community (including benefits of being part of a larger group) and meaning and purpose (including organization’s aspirational reasons for existing). Chen (2022) believes that employees who value work as an identity often portray work as a fundamental part of who they are: they want to live their purpose, causes and beliefs through their work. These employees often find it important for friends and family to know what they work on, as it is a reflection of their identity.

Working remotely during the pandemic crises made people aware that a formal “office as a place” is no longer needed to make work….work. Work is what we do – not where we do it (Wahi et al., 2020). An office can be regarded as a space within a larger work ecosystem (Wahi et al., 2021a). A work ecosystem is a network of connected hybrid and remote First, Second & Third spaces that deliver valuable outcomes through maximizing human contributions as part of a greater specific purpose to fulfill. Each organization has a unique purpose that conveys what the organization does for others ( e.g. customers, clients, citizens, stakeholders and so on).

Within hybrid collaborating organizations, employers need to think of work and life no longer as separate and in competition with each other, but rather ‒ when accommodated successfully ‒ as in harmony (Cambon, 2021, p.27). In the era of work-life separation (1950s -1970s) there were strict boundaries between work and home (Cambon, 2021). The general work-life mindset was: “Don’t bring your personal life /personal stuff to work.” Also due to the lack of computer-based office support, office technology made it quite easy to separate home, work and life. In the era of work-life balance (1980s – 2000), it became easier for the members of the workforce to take work home. Home computers became standard in most households. Overflowing mailboxes and the urge to check your email each day – also in the weekend ˗ caused the rise of the ‘always on – mindset’ being overwhelmed and underway to a burnout. The need for balance often turned into a trade-off (i.e. gaining in one area at the expense of other such as flex-hours) where in the end work always came first.

In the era of work-life integration (2010 -2020), ICT and collaborative software (SharePoint, Google Workspace, Teams, Zoom, Webex, Dropbox and so on) continued to expand the possibilities for how, where and when to work. On-site offices added features such as showers to facilitate lunchtime workouts and kitchens to encourage healthy eating in order to seduce workers to keep on working. A Google employee stated (Lekanne Deprez, 2016): “Other employees complained that there is no such thing as time off. They claim that the benefits of working at Google are an illusion and that their perks are a way to keep you at the office and keep you on track. A culture has been created that an employee feels it is necessary to work on weekends or vacations, though they are not specifically told to” (p.158).” Finally, through work-life harmonization (Cambon, 2021) people will be able to fit in their own (new) ways of working & living into the work-life ecosystem. In a post-pandemic world, life is work; work is life.

Once employees were no longer tied to a physical workplace, managers lost the - close - control that they used to have over employees’ performance and behavior. Management will be fostering an organization-wide culture of trust moving from span of control & narrow supervision to span of support & guidance , empathy, and feedback to really work together in a creative and innovative process to generate concepts, try it out, don’t hold them back, unleash their potential, allow them to fail. (Van der Velden & Lekanne Deprez, 2023). The demands of today’s working environment have reached the point where yesterday’s managers are completely out of their depth. The same approaches that were successful in 2019 are ill-suited for the workforce of 2023. In addition, managers feel pressure from above and below: They must implement corporate strategy with regard to hybrid work, productivity and culture while also providing employees a sense of purpose, emotional support and career opportunities. For an overview of the implications of hybrid working for leadership: see Bergum, Peters & Void (2023) pp. 420 – 422.

References

- Adler, P. S. & Heckscher, C. (2018). Collaboration as an organization design for shared purpose. In: L. Ringel, P. Hiller & C. Zietsma, Toward permeable boundaries of organizations (pp. 81-111), Emerald Publishing Limited.

- Arena, M, Carroll, G., O’Reilly, C., Golden, J. & Hines, S. (2022). The adaptive hybrid. Innovation with virtual work. Management and Business Review , 2 (1), 2 - 9.

- Arena, M. (2023). How to make hybrid work effective, engaging, and empowering. HR best practices based on evidence-based studies and scientific research. https://www.hrexchangenetwork.com/employee-engagement/reports/how-to-make-hybrid-work-effective-engaging-and-empowering

- Battilana, J., Besharov, M., & Mitzinneck, B. (2017). On hybrids and hybrid organizing: A review and roadmap for future research. In R. Greenwood, C. Oliver, R. Suddaby, & K. Sahkin-Andersson (Eds.), The sage handbook of organizational institutionalism (pp. 133–169). Sage Publications. https://doi. org/10.4135/9781446280669.n6

- Battilana, J., & Lee, M. (2014). Advancing research on hybrid organizing: Insights from the study of social enterprises. Academy of Management Annals, 8 (1), 397–441. https://doi.org/10.5465/19416520.2014.893615

- Bershin, J., Spratt, M., Enderes, A.K. & Nangia, N. (2021).The big reset playbook. Deskless worker.pp.1-29. https://joshbersin.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/BigReset_21_10-Deskless-Workers.pdf .

- Bergum, S., Peters, P. & Vold, T.(2023). Epilogue: The future of work and how to organize and manage it, 405 – 433. In: Bergum, S., Peters, P. & Vold, T. (Ed.), Virtual management and the new normal. New perspectives on HRM and leadership since the COVID-19 Pandemic. Palgrave Macmillan Cham.

- Bloom, N . (2023). The future of WFH , Stanford.

- Boughzala, I., & De Vreede, G. J. (2015). Evaluating team collaboration quality: The development and field application of a collaboration maturity model. Journal of Management Information Systems , 32(3), 129–157.

- Buckingham, M., & Goodall, A. (2019). Nine lies about work: A freethinking leader’s guide to the real world. Harvard Business Press.

- Bush M.C. & The great place to work research team (2018). A great place to work for all: Better for business, better for people, better for the world. Berrett Koehler Publishers

- Buggenhout, N., Murat, S. & Sousa, de, T.(2023). Create a virtual watercooler to spark innovative problem – solving. https://www.strategy-business.com/article/Create-a-virtual-watercooler-to-spark-innovative-problem-solving

- Cairncross, F. (1997). The death of distance. How the communications revolution will change our lives. Harvard Business School Press.

- Cambon, A. (2021). From separation to harmonization: The evolving work-life dichotomy. HR Leaders Monthly (March), 24 – 27.

- Capital Global Employment Solutions, (2022 ). Right to Disconnect Legislation in Europe. https://www.capital-ges.com/right-to-disconnect-legislation-in-europe/

- Chen, B. (2022). Understand employee work values for more targeted employee experience improvements, HR Leaders Monthly , December, 44 – 48.

- Chui (2023). Forward thinking on how to get remote working right with Nicholas Bloom, McKinsey Global institute, 1-14.

- Cross, R. (2021). Beyond collaboration overload. How to work smarter, get ahead, and restore your well-being. Harvard Business Review Press.

- Cross, R., & Carboni, I. (2021). When collaboration fails and how to fix it. MIT Sloan Management Review, 62 (2), 24–34.

- Dahl, (2023). Back – with a twist. Korn Ferry Briefings. February/March, 27.

- Davenport, T.H. & Beck, J.C. (2001). The attention economy. Harvard Business School Press.

- Davenport, T.H.(2005). Thinking for a living. Harvard Business School Press.

- De Man, A.-P., Koene, P., & Ars, M. (2019). How to survive the organizational revolution: A guide to agile contemporary operating models, platforms and ecosystems. BIS Publishers.

- Economist (1995). The death of distance. September 30th, 1 – 1995.

- Fjeldstad, Ø. D., & Snow, C. C. (2018). Business models and organization design. Long Range Planning. 51 , 32 – 39.

- Ford, J. & Harding, N. (2004). We went looking for an organization but could find only the metaphysics of its presence. Sociology, 38(4), 815–830.

- Friedman, S. D. (2008). Total leadership: Be a better leader. have a richer life , Harvard Business School Press.

- Future Forum Pulse. (2022, January 25). Leveling the playing field in the hybrid workplace. https://futureforum.com/pulse-survey/

- Gartner (2022). Think hybrid work doesn’t work? The data disagrees. https://www.gartner.com/en/articles/think-hybrid-work-doesnt-work-the-data-disagrees

- Gherson, D., & Gratton, L. (2022). Managers can’t do it all–it’s time to reinvent their role for the new world of work. Harvard Business Review, 100 (3-4), 96-105.

- Gitlab (2021). The remote playbook from one of the world largest all remote companies. Retrieved from https://www.coursehero.com/file/68409096/Gitlab-ebook-remote-playbookpdf/

- Golden, T. D. (2021). Telework and the navigation of work-home boundaries, Organizational Dynamics, 50 (1), 1-10.

- Green, D. (2023). Podcast Daniela Seabrook Philips - How to ensure purpose is at the forefront. Series 29, episode 4. https://www.myhrfuture.com/digital-hr-leaders-podcast/how-to-ensure-purpose-is-at-the-forefront-of-your-people-strategies

- Gullo, F.(2023) We need to expand our definition of hybrid work. https://www.reworked.co/digital-workplace/we-need-to-expand-our-definition-of-hybrid-work/

- Hancock, B., Schaninger, B. & Rahilly,L. (2023). Workplace Rituals: Recapturing the power of what we’ve lost. McKinsey Quarterly , 1-8.

- Huber,C., & Sneader, K. (2021). The eight trends that will define 2021- and beyond, McKinsey & Company , June 2021, 1–8.

- Järvi, H., Kähkönen, A. K., & Torvinen, H. (2018). When value co-creation fails: Reasons that lead to value co-destruction. Scandinavian Journal of Management, 34 , 63-77.

- Jeffres, L. W., Bracken, C. C., Jian, G., & Casey, M. F. (2009). The impact of third places on community quality of life. Applied Research in Quality of Life , 4, 333-345. doi:10.1007/s11482-009-9084-8

- Kelly, K. (2016). The inevitable. Understanding the 12 technological forces that will shape our future. Penquin Books.

- Kraus, S., Bouncken, R.B., Görmar, L., González-Serrano, M. H., Calabuig, F. (2022), Coworking spaces and makerspaces: Mapping the state of research, Journal of Innovation & Knowledge, 7 (1), 1-12.

- Lanning, M.J. (1998). Delivering profitable value. A revolutionary framework to accelerate growth, generate wealth and rediscover the heart of business. Oxford, UK: Capstone Publishing Limited.

- Lekanne Deprez, F.R.E. (1986). Office productivity. Information Services & Use , 6, 83 – 102.

- Lekanne Deprez, F.R.E. (2016). Towards a spatial theory of organizations : Principles and practices of modern organizational design , Unpublished Doctoral Dissertation, Nyenrode Business Universiteit.

- Leonardi, P. (2021). Picking the right approach to digital collaboration. MIT Sloan Management Review, 92 (3), 13–20. Liedtka, J.M. & Parmar, B.L. (2012). Moving design from metaphor to management practice. Journal of Organization Design , 1(3), 51–57.

- Malone, T. W. (2018). How human-computer 'superminds' are redefining the future of work. MIT Sloan Management Review, 59 (4), 34-41.

- Mazzucato, M. (2018). The value of everything: Making and taking in the global economy. Public Affairs.

- McKinsey (2023). Building the office of the future JP Morgan Chase - David Arena and John Means , McKinsey, April 3, 1 – 5.

- Merkel, J., Avdikos, V., Pettas, D. (2023). Coworking Spaces: Alternative Topologies and Transformative Potentials. In: Merkel, J., Pettas, D., Avdikos, V. (eds) Coworking Spaces. Springer, 1- 14. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-42268-3_1

- Microsoft (2021). The rise of the triple peak day. https://www.microsoft.com/en-us/worklab/triple-peak-day

- Microsoft (2021). World trend index. https://www.microsoft.com/en-us/worklab/work-trend-index .

- Mortensen, M & Edmondson, A.C. (2023). Rethink your employee value proposition, Harvard Business Review, 101 (1-2), 45-49.

- Nadella, S. (2021, May 21). The hybrid work paradox. https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/hybrid-work-paradox-satya-nadella/

- Oldenburg, R. (1989). The great good place: Cafes, coffee shops, community centers, beauty parlors, general stores, bars, hangouts, and how they get you through the day. Paragon House.

- Oldenburg, R., & Brissett, D. (1982). The third place. Qualitative Sociology, 5 , 265–284

- Oldenburg, R. (1997). Our vanishing third places. Planning Commissioners Journal, 25: 6–11.

- Oldenburg, R. (1999). The great good place: Cafes, coffee shops, bookstores, bars, hair salons, and other hangouts at the heart of a community . Marlow & Company.

- Peters, T. (2023). Extreme Humanism. Declaration 80 – 20. https://tompeters.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/EXTREME-HUMANISM.Declaration80-20final.pdf

- Pflaeging, N. (2014). Organize for complexity. How to get life back into work to build the high – performance organization . Betacodex Publishing.

- Polman, P. (2023). 2023 Net positive employee barometer: From quiet quitting to conscious quitting. https://www.paulpolman.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/MC_Paul-Polman_Net-Positive-Employee-Barometer_Final_web.pdf /li>

- Polonskaia , A. & Boone , N. (2023).Staying Home to Avoid an Office Flub?. Leadership Korn & Ferry Insights in Leadership. https://www.hrexchangenetwork.com/employee-engagement/reports/how-to-make-hybrid-work-effective-engaging-and-empowering .

- Schultze, U., & Boland Jr, R. J. (2000). Place, space and knowledge work: a study of outsourced computer systems administrators. Accounting, Management and Information Technologies, 10 (3), 187-219.

- Smithuijsen, D. (2023). Verbinding verbroken. Volkskrant , March 26.

- Steelcase 360 magazine (2014).Q+A with Ray Oldenburg. https://www.steelcase.com/research/articles/q-ray-oldenburg/

- Stone, P. J., & Luchetti, R. (1985). Your office is where you are. Harvard Business Review 63(2) 102 – 117.

- Taylor, W.C. (2016). Simply brilliant. How great organizations do ordinary things in extraordinary ways. Random House (UK): Portfolio Penquin.

- Timms, P. (2020). The energized workplace. Designing organizations where people flourish. Kogan Page Limited.

- Velden J. van der & Lekanne Deprez, F.R.E. (2023). Shaping hybrid collaborating organizations (pp.39 – 58).In: Bergum, S., Peters, P. & Vold, T. (Ed.), Virtual management and the new normal. New perspectives on HRM and leadership since the COVID-19 pandemic. Macmillan Cham.

- Wahi, N. et al.(2020). The future of work, part one: Work us an ecosystem. Retrieved from https://www.hksinc.com/our-news/articles/the-future-of-work-part-one-work-is-an-ecosystem/

- Wahi, N. et al.(2021a). The future of work, part two: Eight Characteristics of effective work ecosystems. Retrieved from: https://www.hksinc.com/our-news/articles/the-future-of-work-part-two-eight-characteristics-of-effective-work-ecosystems/ .

- Yang, L., Holtz, D., Jaffe, S., Suri, S., Sinha, S., & Weston, J. & Teevan, J. (2022). The effects of remote work on collaboration among information workers. Nature Human Behaviour, 6 (1), 43–54. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-021-01196-4

- Zack, D. (2015). Single tasking. Get more done ‒ One thing at a time . Berrett- Koehler Publishers.